Small business restructuring: Lessons from the US, UK and India

By: Amanda Bull

In September 2022, the Parliamentary Joint Committee on Corporations and Financial Services was tasked with reviewing Australia’s corporate insolvency laws (“PJC Inquiry”), including the Pt 5.3B small business restructuring regime (“SBR Regime”). Several submissions made to the PJC Inquiry raised concerns with the implementation of the SBR Regime.1

The PJC’s Final Report, issued on 12 July 2023, concluded that although the SBR Regime had been well received, there remained some areas of concern. The issues identified in the PJC Final Report include:2

1. Many small to medium sized enterprises (“SMEs”) are unable to satisfy the eligibility criteria because they have debts that exceed the $1,000,000 debt threshold;3

2. Some SMEs are excluded from progressing to the restructuring plan phase of the SBR Regime because they are unable to pay all of the outstanding employee entitlements (including superannuation) and/or are unable to substantially comply with their taxation obligations;4 and

3. The SBR Regime remains too expensive for some SMEs.

The PJC Inquiry recommended that the federal government review the operation of the SBR Regime having regard to, amongst other things, the approaches adopted in foreign jurisdictions.5

This article examines analogous legislative frameworks in the United States of America (“US”), the United Kingdom (“UK“), and India.

Subchapter V of the United States Bankruptcy Code

In February 2020, Subch V was incorporated into Ch 11 of the United States Code (‘USC‘). Much like the Australian SBR process, the US Subch V approach was intended to reduce the costs and duration of the Ch 11 process for SMEs and to assist inexperienced SME directors to formulate a restructuring plan with the assistance of a qualified trustee.6 The appointment of a trustee was a significant divergence from the Ch 11 regime.

(1) Debt limits in eligibility criteria

Subchapter V requires the SME debtor to be engaged in commercial or business activity with debts below $USD7,500,000. Unliked the SBR Regime, this amount includes both secured and unsecured debts, but excludes debts owed to related parties.7 The debt limit was also originally set at $USD2,725,625 but was temporarily increased in 2020 to $USD7,500,000. 8 That increased threshold is due to expire on 21 June 2024. Whilst calls have been made to permanently raise the debt limit to this amount,9 it remains uncertain whether Congress will enact this change on a permanent basis.

(2) Who’s in control?

In an attempt to reduce costs and overall duration of the regime, Subch V has removed the need for a creditors’ committee, instead appointing a trustee to supervise the process.10 The removal of the committee of creditors has enabled a restructuring plan to be approved without the confirmation of any creditors and for nonconsenting creditors to be “crammed down”.11 Congress made these changes to address the fact that creditors in SME cases do not have claims large enough to warrant the time and money to actively participate. 12

(3) Trustee’s obligations

In a further attempt to curtail costs, the Subch V trustee is not under a duty to investigate the financial affairs of the debtor SME.13 Instead the SME directors remain responsible for disclosure obligations,14 whilst the trustee is appointed to assist the inexperienced directors to work towards the consensual confirmation of a restructuring plan.15

(4) Creditors’ meetings

Subchapter V removes the need for creditors’ meetings but requires the Court to hold a status conference no later than 60 days after the Subch V process has commenced, with the SME debtor to serve and file a report outlining its efforts to enter a consensual restructuring plan no later than 14 days prior to the status conference.16. To further curtail costs Subch V eliminates the “absolute priority rule”.17 This rule is intended to protect creditors in a standard Ch 11 by requiring that secured creditors be paid in full before unsecured creditors and unsecured creditors be paid in full before equity creditors. This can result in the directors losing their interest in the SME, which is problematic because SME directors are usually a crucial part of the business.18 Instead, Subch V debtors can “cramdown” restructuring plan terms on non-consenting creditors, while retaining their equity interest.19 This change reduces costs compared to a standard Ch 11 as the debtor no longer has to try to obtain accepting votes from at least one class of impaired creditors.20 This change is seen by many as the single biggest difference between Ch 11 and the new Subch V process.21

(5) Timeframe

Finally, the Subch V regime proceeds relatively quickly compared to Ch 11.22 The regime requires that the SME debtor file a restructuring plan no later than 90 days after the Subch V appointment, and only permits extension of this timeframe by the courts if the need for the extension is outside the debtor’s control.23.The duration of the restructuring plan is limited to a maximum of five years.24

(6) Statutory Review

The American Bankruptcy Institute has established the Subch V Task Force to review the implementation and administration of Subch V.25 The Task Force has held several virtual public hearings with bankruptcy judges, practitioners and Subch V trustees in relation to their experiences with Subch V.26 The Task Force is due to hand down its final report in June 2024.27

The UK’s Company Voluntary Arrangement (“CVA”) Regime

A CVA is best described as a commercial agreement proposed by a company to its creditors setting out how the directors plan to rehabilitate the company and deal with creditor claims.28 Although the CVA is not limited to SMEs, they are seen as “predominantly a small-firm affair. “29

There is a second regime that is available to SMEs known as the Restructuring Plan. The Restructuring Plan was, much like the SBR Regime, rushed through parliament as part of the UK’s emergency COVID-19 measures.30 The Restructuring Plan was intended to facilitate an efficient rescue of a financially distressed company that would benefit all company stakeholders, keep administrative burdens to a minimum, make the process as quick as possible and not add disproportionate costs to the already struggling business.31

A third standalone statutory moratorium is available to SMEs. This statutory moratorium was also introduced as part of the UK’s emergency COVID-19 measures. This “one size fits all” moratorium replaced the small business moratorium previously contained in the CV A.32. It is intended to provide companies, irrespective of size, with some additional breathing space to get the business restructure across the finish line.33

Although the Restructuring Plan has been used successfully for some SMEs,34 the CVA process is still perceived as a more cost-effective option for SMEs.35 As a result, it is more commonly used by SMEs in financial distress. It is for this reason that this article focusses on the CVA and the standalone statutory moratorium.

(1) Debt limits in eligibility criteria.

Unlike the other regimes considered in this article, the only eligibility criteria for the CVA is that the directors and members agree for the SME to enter the CVA process.36 This is reflective of the fact that the CVA process is available to companies of any size; not just SMEs.

(2) Who’s in control?

The CVA regime enables the debtor to remain in possession during the CVA process. It is therefore the directors’ role to prepare the restructuring plan.37 The nominee (akin to the restructuring practitioner in the Australian SBR Regime) is responsible for assisting the directors to develop and implement the proposal (similar to the Australian restructuring plan) and supervise its implementation.38 Although the proposal must be lodged with the court, the court’s role is purely administrative at this stage of the CVA process.

(3) Trustee’s obligations

Much like the Australian SBR Regime, the nominee is not required to undertake detailed investigations into the SME’s financial position. Instead, the nominee can rely on the information provided by the SME directors in the form of a statement of affairs. 39 Notwithstanding this fact, the nominee must still be satisfied that the SME’s assets and liabilities are not substantially different from the position put forward in the proposal and that the proposal has reasonable prospects of being approved and implemented.40 As a result, the nominee is often given access to the SME’s books and records for this purpose.41

The nominee must also identify any possible antecedent transactions undertaken by the company.42These include sales at an undervalue and preference payments.

(4) Creditors’ meetings

There is no obligation to hold a physical meeting of creditors.43 Rather, a proposal will be approved if a simple majority of the shareholders and three-quarters in value of those unsecured creditors that are present, and voting agree to its terms ( and the plan is not opposed by more than 50% of unrelated creditors).44

The CVA contains a “cramdown” whereby dissenting creditors are bound by the majority (in value) view, voting to adopt the terms of the proposal.44 Unlike the US regime, but akin to the SBR Regime, creditors are placed into a single class rather than dividing them into numerous classes.46 Similarly to the Australian SBR Regime, once approved, the plan is binding on all creditors that had notice of the meeting and were entitled to vote; however, secured creditors and preferential creditors must have agreed to the proposal for it to be imposed on them.47

Approval of the proposal converts the nominee into the supervisor, who is then charged with ensuring the plan is given effect.48

(5) Timeframe

The total timeframe for the proposal of a proposal is between six to eight weeks. The timeframe commences upon the appointment of a nominee. Once appointed, the nominee has four weeks from the date of appointment to create and put forward a proposal to creditors. Once the proposal has been provided to creditors, they have 14 days, and no more than 28 days, to vote on it.49 If approved the nominee then has four days to lodge the proposal and report the result of the shareholders’ and creditors’ decision to the Court.50 The duration of the proposal is usually between two to five years, although some last for more than five years to facilitate the payment of the SME’s creditors.

(7) Statutory Review

The CVA, Restructuring Plan and Statutory Moratorium have been the subject of scrutiny following their implementation. The report into CVAs was issued in May 2018 and the Final Evaluation Report for the Restructuring Plan and Statutory Moratorium was published on 19 December 2022.51. The findings from those reports were generally positive but noted some confusion amongst practitioners in relation to the drafting of the Restructuring Plan and Statutory Moratorium and recommended some further simplification measures. Most notably certain aspects of the Statutory Moratorium were seen as complex and unhelpful, and the overwhelming majority of respondents considered the Restructuring Plan too expensive for use by the SME market.52

The UK’s insolvency laws have had a significant influence on the creation of India’s insolvency framework.

India’s Insolvency and Bankruptcy Code and Pre-Packaged Insolvency Resolution Process (“PPIRP”).

India is an interesting jurisdiction to consider in a comparative sense because it has a colonial history coupled with an economic and legislative focus on micro and small businesses.53 The Insolvency and Bankruptcy Code 2016 (“IBC”) provides a statutory rescue mechanism for both companies and individuals in financial distress. The most relevant for SMEs is known as the Pre-Packaged Insolvency Resolution Process (“PPIRP”). The PPIRP is intended to provide micro businesses and SMEs with a faster, more cost-effective regime that maximises value for all stakeholders in the least disruptive manner. It is said to be both informal (in the pre-admission phase) and formal (in the post-admission phase).54

(1) Debt limits in eligibility criteria.

An SME is eligible to initiate the PPIRP process if it has committed a default of at least 10 Lakh Rupees (equivalent to approximately $AUD182,000), is eligible to submit a resolution plan,55 and has not undergone a PPIRP within the last three years or is currently not undergoing, or has not undergone in the past three years, a related procedure known as a Corporate Insolvency Resolution Procedure.56

(2) Who’s in control?

The IBC allows management and major shareholders to remain in control of the SME, with lenders retaining extensive oversight of the PPIRP.57 However, unlike the SBR Regime, the Indian PPIRP retains a committee of creditors (“CoC”).58 To mitigate delays associated with improper creditor conduct, the Insolvency and Bankruptcy Board of India, together with the Insolvency Law Academy, created a voluntary Code of Conduct that is intended to govern the CoC’s conduct whilst making decisions under the IBC.59

(3) Trustee’s obligations.

In a departure from the other jurisdictions, the scope of the resolution professional’s role remains quite expansive under the PPIRP.60 The resolution professional is required to verifying creditor claims, monitor management of the SME, inform the CoC regarding any statutory breaches by the directors, constitute the CoC and prepare various documentation, including the information memorandum61 required by the IBC.62

(4) Creditors’ meetings.

India is the only jurisdiction considered by this article to retain a CoC. The CoC retains significant control over the PPIRP process. The CoC is initially appointed by the resolution professional.63 During the meeting of creditors, the CoC will be required to consider the resolution plan put forward by the SME together with any alternate plans.64 The CoC may approve any or none of the proposed resolution plans.65

(5) Timeframe.

The prescribed period for a PPIRP is 120 days (4 months) from the date of commencement.66 The resolution professional is required to submit an approved resolution plan to the National Company Law Tribunal within 90 days of the commencement of the PPIRP, allowing them a further 30 days to consider the restructuring plan.67 This condensed timeframe was implemented on the basis that the less time the company spends in the rehabilitation process the more likely it will be to retain “enterprise value”, suffer the least disruption to business continuity and preserve jobs.68

(6) Statutory Review.

The PPIRP is also the subject of a government review. The review process is, amongst other things, considering whether the PPIRP should be expanded to a broader range of companies beyond SMEs.69

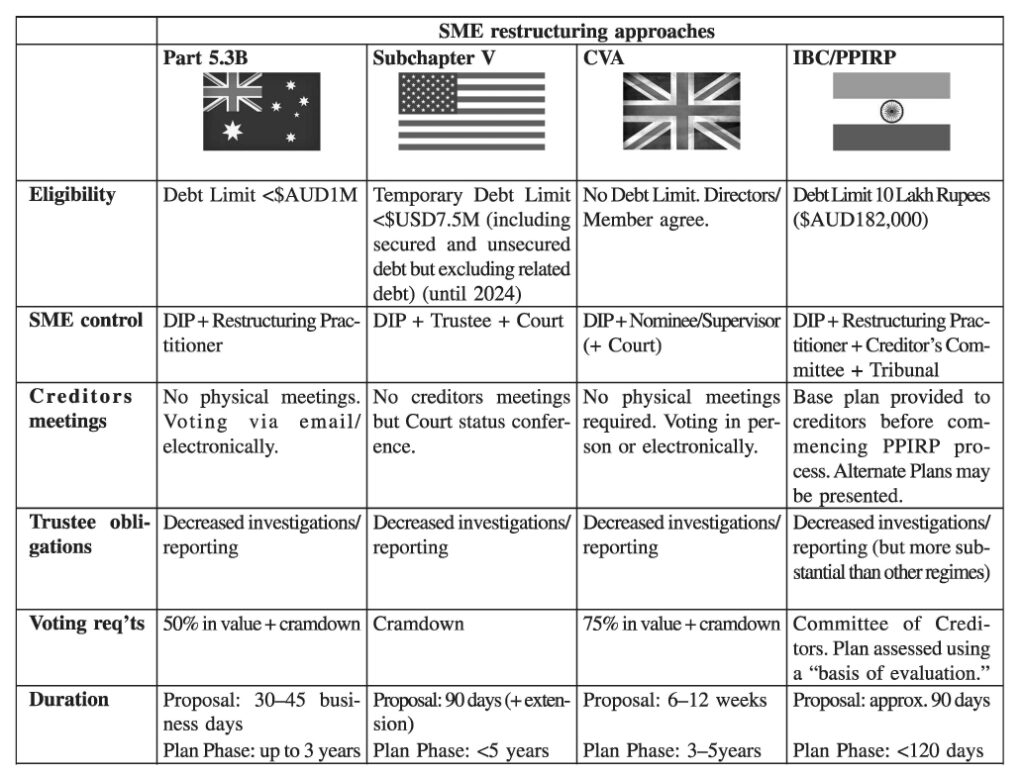

For ease of comparison, Table 1.1, summarises the information discussed in this article.

Table 1.1

Conclusion

This article has demonstrated that whilst SME specific rescue laws can be found in many jurisdictions around the world,70 they have all been implemented in slightly different ways to suit their existing legislative framework, the characteristics of their SME sector, and their broader economic context. Australian policymakers and legislative drafters must therefore take care to identify those jurisdictions that most closely align with the Australian position. It is for these reasons that this article has drawn on the experiences of the US, UK and India.

The UK and US were chosen as comparators because the US Ch 11 regime ( out of which its SME-specific Subch V evolved) has been consistently raised by Australian policymakers and academics as an alternative basis upon which the Australian SBR Regime could be based.71 The UK regime was chosen because its insolvency framework was the model upon which the Australian framework was initially developed. Further, the UK regime demonstrates how a traditionally creditor focussed insolvency framework can be amended to better suit rescue of viable corporations. The Indian regime is a useful third comparator as its legislative framework is based on a long history of legislating to protect micro to-small businesses, albeit not always in an insolvency framework.

Despite shared characteristics across these regimes, the ongoing reviews of most systems suggest that none currently operate at an optimal level. As we navigate the complexities of our own regime, perhaps a prudent approach is to carefully observe the outcomes of these reviews before contemplating adjustments. This “wait and see” strategy will enable us to make informed decisions informed by the evolving landscape of global small business restructuring practices

*Ms. Amanda Bull, Lecturer, Queensland University of Technology.

Footnotes

- Parliamentary Joint Committee on Corporations and Financial Services, Corporate Insolvency in Australia (Commonwealth of Australia, July 2023) 45 (“P JC Final Report”). For background on the Australian and Indian position see further, Jason Harris and Preeti Nalavadi, “One size doesn’t fit all? Comparing insolvency law reforms for MSMEs in Australia and India” (2023) 22(8) Insolvency Law Bulletin 109.

- Ibid 130–131 [7.52], [7.54]; Australian Securities and Investment Commission, Review of Small Business Restructuring Process (Report No 756, 17 January 2023) 4-5; CPA Australia Ltd, Submission No 11 to the Parliamentary Joint Committee on Corporations and Financial Services, Inquiry into Corporate Insolvency in Australia (29 November 2022) 2.

- The eligibility criteria can be found in Corporations Act 2001 (Cth) s 453B; Corporations Regulations 2001 (Cth) reg 5.3B.03 (“Corporations Regulations”).

- The requirement for payment of employee entitlements and compliance with tax obligations can be found in: Corporations Act 2001 (Cth) (n 3) s 455B; Corporations Regulations (n 3) reg 5.3B.23.

- Parliamentary Joint Committee on Corporations and Financial Services (n 1) 146 [7.107].

- Brook Gotberg, “Small Business Restructuring: The US Experience” (Online, 21 March 2023); Jill C Walters, William D

Curtis and Womble Bond Dickinson, “Subchapter V vs ‘Ordinary’ Ch 11 Practice Changes for Small Business Debtors” 5. - 11 USC 2022 (USC) § 1182(1)(A) (definition of “debtor”).

- Coronavirus Aid, Relief, and Economic Security Act of 2020, Pub L No 116-136, 134 Stat 281 (2020) (“CARES Act”);

extended by a year by: COVID-19 Bankruptcy Relief Extension Act of 2021, Pub L No 117-5, 135 Stat 249 (2021), and

extended for a further two years by Bankruptcy Threshold Adjustment and Technical Corrections Act of 2022, Pub L

117-151, 136 Stat 1298 (2022). - Since the debt-eligibility limits were increased by the CARES Act in March 2020, about 30 percent of the subchapter V cases filed have been over the original debt limit: American Bankruptcy Institute, “What’s Happening at ABI” (2023) 42(6) American Bankruptcy Institute Journal 45.

- The Small Business Reorganization Act of 2019, Pub L No 116-54, 133 Stat 1079 § 1183(a), (2019).

- Cramdown enables a debtor SME to force a Restructuring Plan on creditors who are unwilling to agree to it voluntarily USC § 1191 and §1129(b)(2)(a)(i) (2022).

- The Small Business Reorganization Act of 2019, Pub L No 116–54, 133 Stat 1079; § Walters, Curtis and Dickinson

(n 6) 2. - Unless the Court orders that it do so after receiving a request from an interested party: 11 USC §1183(b)(2), §1106(a) and

§704 (2022). unless the Court orders that it do so after receiving a request from an interested party 11 USC (n 7) §1183(b)(2), §1106(a) and §704. - Ibid §1183, §1187, §1190(a)(l).

- Ibid §1183(b); Walters, Curtis and Dickinson (n 6) 4.

- USC §1188 (2022).

- 11 USC (n 7) § 1129(b )(2)(a)(i).

- 11 use §1129(b)(2)(a)(i) and §1129(b)(2)(a)(i) (2022).

- Gotberg (n 6).

- 11 USC §1129(a)(l) (2022).

- Walters, Curtis and Dickinson (n 6) 3.

- 11 USC §112l(e) (2022).

- 11 USC § 1189(b) (2022).

- 11 USC § 1192 (2022).

- American Bankruptcy Institute, “ABI Subchapter V Taskforce”, American Bankruptcy Institute Subchapter V Taskforce Homepage (2023) <https://subvtaskforce.abi.org/>.

- Ibid

- American Bankruptcy Institute (n 9) 47.

- Lorraine Conway, Company Voluntary Arrangements (CVAs) (Briefing Paper No 6944, 11 June 2019) 3.

- Naresh R Pandit et al, “Corporate Rescue: Empirical Evidence on Company Voluntary Arrangements and Small Firms” (2000) 7(3) Journal of Small Business and Enterprise Development 241, 250; Peter Walton, Chris Umfreville and Lezelle Jacobs, Company Voluntary Arrangements: Evaluating Success and Failure (Report, R3, May 2018) 93, 15.

- The Corporate Insolvency and Governance Act 2020 (UK) (“CIGA”) received Royal Assent on 25 June 2020 and came into force on 26 June 2020 after a very quick legislative process that lasted just over 1 month: UK Parliament, “Corporate Insolvency and Governance Act 2020 Stages”, UK Parliament <https://bills.parliament.uk/bills/2739/stages>.

- Jennifer Payne, “An Assessment of the UK Restructuring Moratorium” (SSRN Scholarly Paper, 4 January 2021) 6 <https://papers.ssrn.com/abstract=3759730>; Explanatory Notes, Corporate Insolvency and Governance Act (UK) 2020 4 [5]-[6].

- Insolvency Act 1986 (UK) Sch Al, s 3; Companies Act 1985 (UK) s 247(3).

- “Explanatory Notes, Corporate Insolvency and Governance Act (UK)” (n 31) 4–5.

- see, for example, “Roust Ltd, Re [2022] EWHC 1941 (Ch) (22 July 2022)”.

- The Insolvency Service, Corporate Insolvency and Governance Act 2020 Final Evaluation Report (The Insolvency

Service, 19 December 2022) [4.2.2]. - Insolvency Act 1986 (n 32) Pt I, s 1(1).

- Gabe Harley, “The CVA Process from Preparation to Decision” in Elaine Nolan and Tom Smith QC (eds), Company Voluntary Arrangements (Oxford University Press, 2022) 0, [5.27]-[5.39].

- Ibid [5.05]-[5.26].

- Insolvency Act 1986 (n 32) Pt I s 2(3).

- The requirement to provide a nominee’s report to Court does not apply in situations where the SME is already in liquidation or administration: (s 2[1] ibid Pt I, s 2).

- Harley (n 37) 145 [5.20].

- Insolvency Act 1986 (n 32) ss 238, 239, and 245.

- Insolvency (England and Wales) Rules 2016 (UK) r 15.3 and 15.4.

- Insolvency Act 1986 (n 32) ss 2(2), 3(1), 249 (when a creditor is related); Insolvency (England and Wales) Rules (n 43) reg 15.34(3); Harley (n 37) [5.84].

- Ian F Fletcher, “UK Corporate Rescue: Recent Developments – Changes to Administrative Receivership, Administration, and Company Voluntary Arrangements – The Insolvency Act 2000, The White Paper 2001, and the Enterprise Act 2002”

(2004) 5(1) European Business Organization Law Review 119, 127. - Ibid.

- Insolvency Act 1986 (n 32) ss 4(3) and 4(4).

- Ibid s 7(2); Insolvency (England and Wales) Rules (n 43) r 15.3l(d) (explains the date from which the debt is to be

calculated for these purposes). - Insolvency (England and Wales) Rules (n 43) r 2.26(3) (members) and r 2.27 (creditors); In practice, 17 days between

appointment and the meeting is common to allow for service of the meeting notices: Harley (n 37) 154 [5.50]. - Insolvency Act 1986 (n 32) Pt I s 4(6A).

- Walton, Umfreville and Jacobs (n 29); The Insolvency Service (n 35).

- The Insolvency Service (n 35).

- See, for example, The Micro, Small and Medium Enterprises Development Act, 2006 (India) (aimed at creating a single comprehensive Act for the development and regulation of small enterprises. This legislation also created the Micro and Small Facilitation Committee to adjudicate disputes in relation to delayed payments to MSMEDs); Reserve Bank of India, Guidelines for Rehabilitation of Sick SME Units (September 2011); Reserve Bank of India, “Master Circular – Lending to Small & Medium Enterprises Sector (SMEs)” (“July 2016”); Reserve Bank of India, “Master Circular – Lending to Micro, Small & Medium Enterprises (MSME) Sector” (“July 2008”); Reserve Bank of India, “Master Circular – Lending to Micro, Small & Medium Enterprises (MSME) Sector” (“July 2012”).

- Insolvency and Bankruptcy Board of India, “Pre-Packaged Insolvency Resolution Process: Information Brochure” I <www. ibbi.gov.in/uploads/whatsnew/a650764a464bc60fe330bce464d5607d.pdf>.

- Insolvency and Bankruptcy Code, 2016 (India) 29A (‘IBC’) (essentially a debtor is ineligible to put forward a resolution

plan if they are an undischarged insolvent, a willful defaulter or otherwise in default). - Ibid s 54A.

- Insolvency Law Committee, Report of the Insolvency Law Committee (Ministry of Corporate Affairs, Government of

India, May 2022) 1, 1.5; Insolvency and Bankruptcy Board of India (n 54) 2. - IBC (n 55) s 54H (directors remain in control) and s 541 (committee of creditors).

- Insolvency Law Academy, Committee of Creditors: Statement of Standards in Conduct and Performance for Creditors

(February 2023). - A resolution professional under the IBC is similar to a restructuring practitioner under the SBR Regime.

- “Information Memorandum” is one of the most important documents under the PPIRP. It provides the basis for preparing the resolution plan and includes a list of creditors and their claims, related party debt, number of employees and their entitlements, details of any material litigation, the latest audited financial statements and audited financial statements for the last two years, provisional financial statements, liquidation value etc Institute of Insolvency Professionals, “IBC Knowledge Capsule 22: Framework for Information Memorandum under IBC”.

- IBC (n 55) 54F.

- There is no definition of “resolution professional” contained in the Act. However, see ibid s 54B; The CoC is comprised of the SME’s unrelated financial creditors. Ibid s 54F and s 541 If there are no unrelated financial creditors then the committee will be made up of unrelated operational creditors who will perform the same duties and functions as the unrelated financial creditors.

- IBC (n 55) 54K and 54L. This approach is similar to the US Chapter 11 (excluding subchapter V) requirements: USC 11

§ 112l(b)-(c) (2022). - The CoC uses a “basis of evaluation” in accordance with the requirements set out in the regulations: Pre-Packaged Insolvency Resolution Process Regulations, 2021 reg 42 (“PPIRP Regulations”).

- IBC (n 55) s 54D.

- Ibid 54D(2)

. - Sub-Committee of the Insolvency Law Committee, Pre-Packaged Insolvency Resolution Process (Ministry of Corporate Affairs, Government of India, 31 October 2020) 1, 1. 7, 1.14, 1.20 and 2.15.

- Government of India, Ministry of Corporate Affairs, “Notice: Invitation of Comments from the Public on Changes Being

Considered to the Insolvency and Bankruptcy Code, 2016″. - There are SME specific regimes in a number of other jurisdictions including the Netherlands, Spain, Germany, Denmark, Finland, Sweden, Japan, South Korea and Singapore. For a detailed consideration of some of these regimes see: World Bank Group, Saving Entrepreneurs, Saving Enterprises: Proposals on the Treatment of MSME Insolvency (World Bank, 17 September 2018) 11-14, 30 (Argentina, India, Greece), 31 (Japan) and 32 (Republic of Korea). See also, Aurelio Guerra Martinez, “Implementing an insolvency framework for micro and small firms” (2021) 30 International Insolvency Review S46.

- Ahmed Terzic, “Turning to Chapter 11 to Foster Corporate Rescue in Australia” (2016) 24 Insolvency Law Journal 26;

Australian Government, National Innovation and Science Agenda Improving Bankruptcy and Insolvency Laws (Proposals Paper, April 2016).

This article was originally published by LexisNexis in the Insolvency Law Bulletin (Issue 22.9&10).